The Mortifying Ordeal of being Online

On being Online for work & balancing one's mental health

Hello my loves,

I wrote this newsletter after having had a sort of offline day. For the last month, I’ve made a conscious effort to use my phone less for one day a week, usually on a weekend or a Monday. A sort of offline day means that I don’t post anything for at least 24 hours, turn off notifications, and turn on do not disturb mode. I still allow myself to reply to messages, browse online and scroll on my FYP, in moderation, because Absolutes Do Not Work For Me. It only took me 28 years to learn that Absolutes Do Not Work For Me, personally. When I delete all social media apps, social media is all that’s on my mind. Taking a sort of break has helped reduce my screen time overall without making me feel like I’m missing out too much. And at the risk of sounding like that person who always announces that they’re off social media for their mental health and to text them if you need them… I’m kind of off social media (for about a day per week) for my mental health.

Earlier this year I deleted my 9-5 office job to focus on social media full time. I was burned out from working two jobs and felt ready to take the leap to be a freelancer. Once I did the numbers and realised that I would be able to make almost as much from my combined content jobs, as I did from my 9-5 I handed in my resignation. The fact that all of this happened thanks to a social media app some legislators want to make illegal is still surreal to me.

I joined my first social media platform I was 12. I signed up for game/ chat forum that I could only use when I visited a friend who had a computer in her room and parents who didn’t care what we did on it. I have no idea what this forum is called anymore, but remember that my password was “IloveOrangeJuice”. When I was 14, I joined WerKenntWen, a German social media site often compared to MySpace. “Wer Kennt Wen” roughly translates to who knows whom and allowed me to add everyone I went to high school with. I’d check my messages at the school library computer because we didn’t have an internet connection at home (my mum was a luddite Jehovah’s Witness and worried I would be corrupted by the internet. She was right). This meant that I wouldn’t be online at the same time as anyone I wanted to chat to. I never experienced the excitement of hearing MSN messenger alerting me to a new message, or used Omegle while underage. It was only when I created a Facebook and Twitter accounts a year or two later that I really started interacting with people, and sharing my own posts. I’d scroll through everyone’s innermost thoughts and add my own, which Facebook loves to remind me with its “On this Day” feature.

So before I was a content creator, I was a content consumer. When I first started spending time online, the internet felt like my quiet place, where I could spend hours researching my niche interests as a teen. I’d watch music videos on YouTube and read beauty reviews on Into The Gloss, got style inspiration from The Sartorialist and read feminist humour pieces on The Toast. I’d visit individual websites to catch up on the latest posts from my favourite bloggers, obsessively reposted outfits and interiors on tumblr and watched shorts on Nowness. I didn’t yet know that I’d have a career in social media, but I knew that being I loved being online.

My online content creation ~journey~ started in the Covid-19 pandemic, when almost everyone I knew downloaded TikTok. I’d gotten an agent in the few months between the first, and second pandemic lockdowns in Melbourne. We caught up for a coffee before she signed me. She asked me about my dreams and I mentioned two things: Writing a book, and quitting my job. That’s easy, Lena said. All you need is 50,000 followers, and you’d make just as much as you do in your 9-5, she said. I sipped my oat latte and looked at my follower count of ca. 2,000 and thought ok, just 48,000 to go.

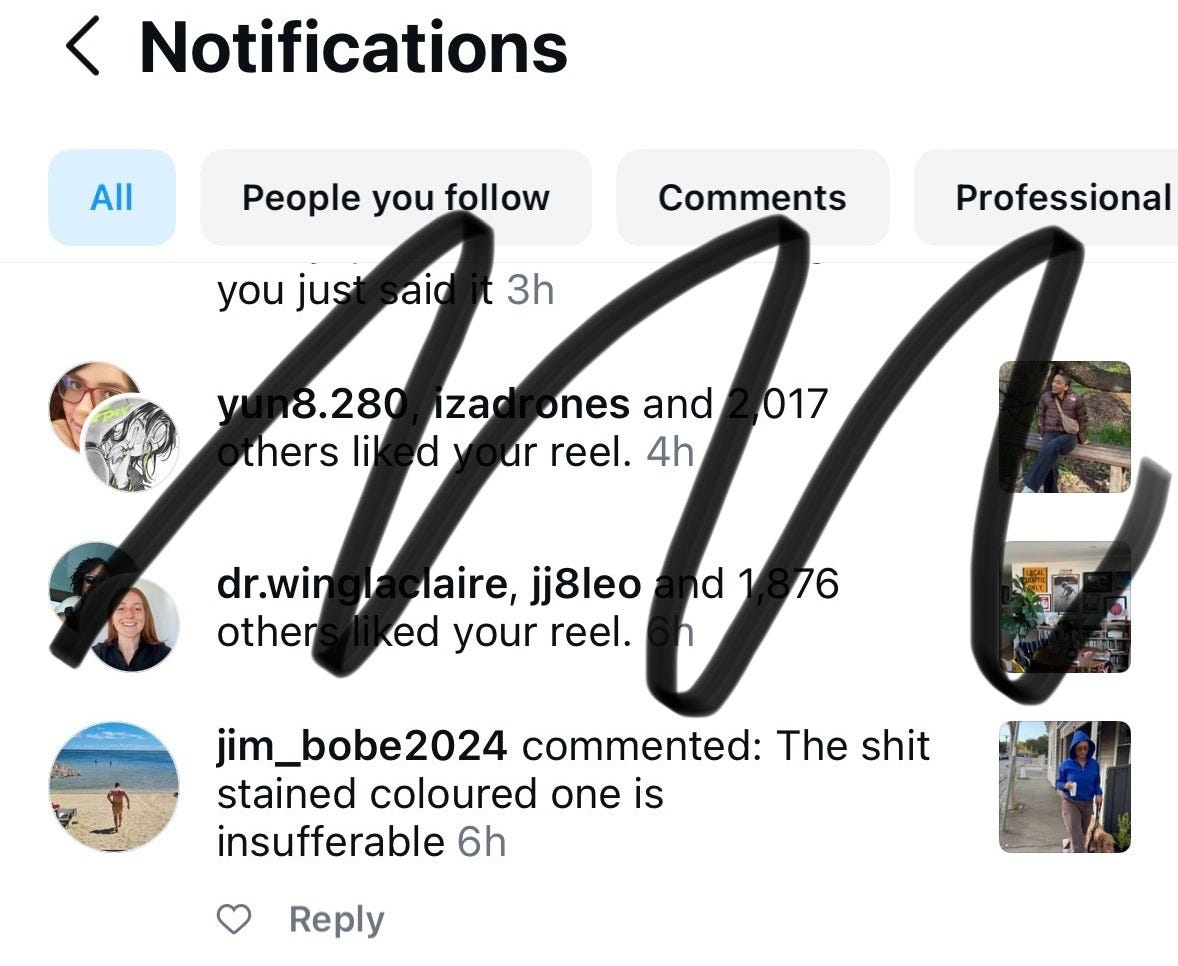

At this stage, the pandemic had forced us to connect with each other through our screens for months. We had school on Zoom, work on Zoom, catching up with friends on Zoom. Social media apps fostered a sense of community and fun in a time of uncertainty and loneliness. We followed the same whipped coffee recipe, made that viral one pan cheesy pasta and tried to learn dance choreography for 15 second pop songs that seemed to be written specifically for the algorithm. When I wasn’t able to do stand up comedy live, I started saying the things I would on stage into the front-facing camera of my phone, uploading the videos to TikTok and the then newly launched Instagram reels. I started sharing more of my life online, too. My interior design obsession, videos of my dog, videos where I’m mixing cocktails or rambling at the camera and comedy sketches with my wife. And then, the numbers started growing. Since I first posted video content in 2021, my videos have accumulated millions of views and likes. I’m by no means a “big” account; while I hit my 50k goalt his year, I’d be classified as a micro influencer. My videos go small town viral sometimes, my numbers don’t compare to the accounts with millions of followers, and I’m glad about it. Because I can hardly take the racism, sexism and homophobia that my videos attract once the algorithm pushes them the discovery page. Here’s an example from a skit my wife and I made about our favourite suburbs in Melbourne:

When I saw this comment, it felt like a punch in the gut. I deleted the notification, but not the comment itself. It was the weekend, when I try to prioritise quality time with my wife, and my time sort of away from my phone. I didn’t even want to bring it up with Tamara, feeling like I’d bring down the mood and make both us angry. But later that day, I heard her say “bastards!” she turned her screen to me and showed me that she’d flagged jim_bobe2024’s comment with Meta, and they deemed it A-OK.

Whenever I share vile comments like this, I get well-meaning responses from people who think I shouldn’t give this type of hate any air. And while that was my own instinct at first, I also need you to know that I receive way more bigoted comments than I share. When you need to spend time on social media for work, the comment section is an extension of your workplace.

I was at a brand lunch the other day, talking about the things we see in our comment sections with other content creators and social media managers. Someone suggested blocking certain keywords, which is something I’m thinking about. It’s just that bigots have gotten so creative with their language and insults that blocking words like “black” “gay” or “queer” wouldn’t really do much. Another BIPOC content creator empathised with the struggle of comment moderation, and fear of putting yourself out there when it has the potential to wreck havoc on your mental health. We didn’t find a solution, but the solidarity of the moment has stayed with me.

I’m struggling to find a neat way to tie up this newsletter, because there isn’t one. I’ve been writing about how it feels to be online at the moment in my notes and journal for a while, but seems like every time I’ve come close to hitting publish, the online landscape has changed; usually for the worse. I’m slowly accepting that my writing won’t always be as “complete” as I want it to be - but published is better than perfect.

So I’ll leave you here for now, in hopes that we can both strike a healthy balance between being online and offline. A reminder to be gentle with yourself, and to hit that block or delete button liberally <3

Talk soon!!

I love you so much xx

Aurelia

Hey Aurelia, Academic and ex journo Emma A Jane has done some amazing research and writing about the vitriol men spew towards women online after being a target of online rape harassment herself. Keep being the wonderful creator you are - you and Tamara are my fave lezzo couple online. I mean - the joy and LOVE! Also, that shit stain is likely covered in them. As is meta. 💗